Sharding high-throughput Redis without downtime

Read about how we rolled our new sharded infrastructure out to production without a millisecond of downtime and how it improved Inngest's overall performance.

Bruno Scheufler· 7/23/2024 · 13 min read

Every day, more and more software teams rely on Inngest for their core infrastructure which results in increased load on our core systems. When building distributed systems, vertical scaling can only get you so far. Because of that, we took on a project to horizontally scale by sharding our most crucial database, which serves more than 50,000 requests per second at low latency. As Inngest is critical infrastructure for many customers, we aim to avoid maintenance windows at all costs. In this post we’ll walk through how we sharded our function state database with zero downtime.

Inngest Architecture Primer

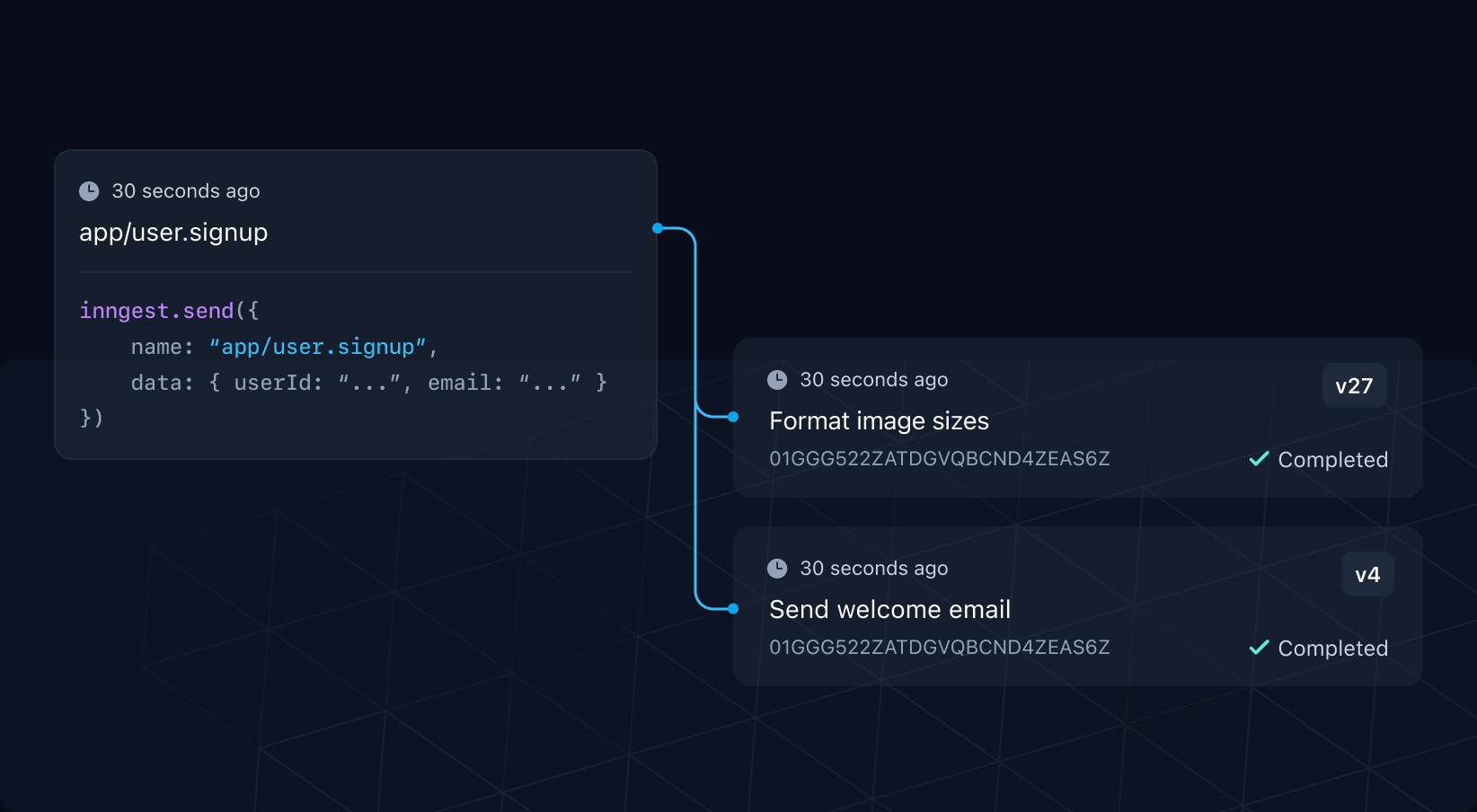

Inngest enables developers to write durable functions with flow control. To reliably execute long-running functions, function state is stored within Inngest to resume and retry functions without losing execution progress. This state must be stored at low latency, but persisted indefinitely. Functions might execute for seconds or months. Function state, including user-generated output, can grow over time, yet we need to ensure consistently high performance. On an average day, we serve hundreds of millions of events.

Until now, this immense volume of queue and state data was stored in our highly-available production data store based on Redis, which persists data to disk for fault tolerance and is optimized for low-latency data access, handling more than 50,000 operations per second. To avoid degrading performance in our production environment due to high latency or failing operations, we have robust monitoring and observability infrastructure in place to spot trends ahead of time. From May onward, we observed accelerating usage of Inngest Cloud. Redis processes requests on a single thread. At high CPU usage, this can lead to high request latency.

To alleviate the limitations of running a single Redis cluster, we planned medium to long-term infrastructure improvements based on Q2 growth estimates. However, we did not anticipate the uptick in product usage caused by onboarding many new enterprise users in June. This sudden success overwhelmed all our forecasts and gave us a reason to act swiftly. Luckily, we had been working on adjacent projects since May, allowing us to switch gears and shift our focus to immediate improvements.

However, there's a catch: Because Inngest is a reliable foundation for so many applications, we can't introduce downtime for migrations so shutting down parts of our system even for a few minutes is out of the question. So, what can we do?

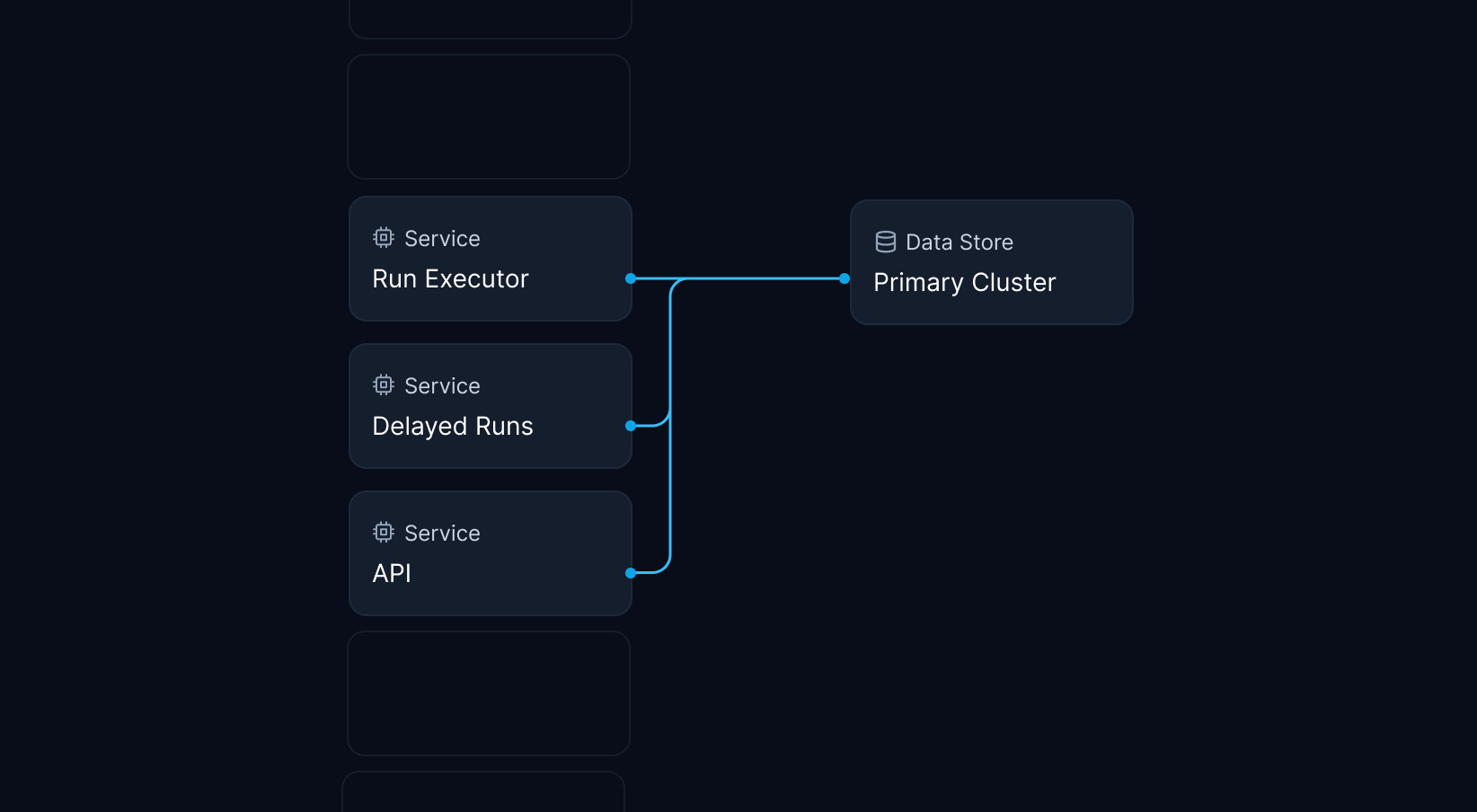

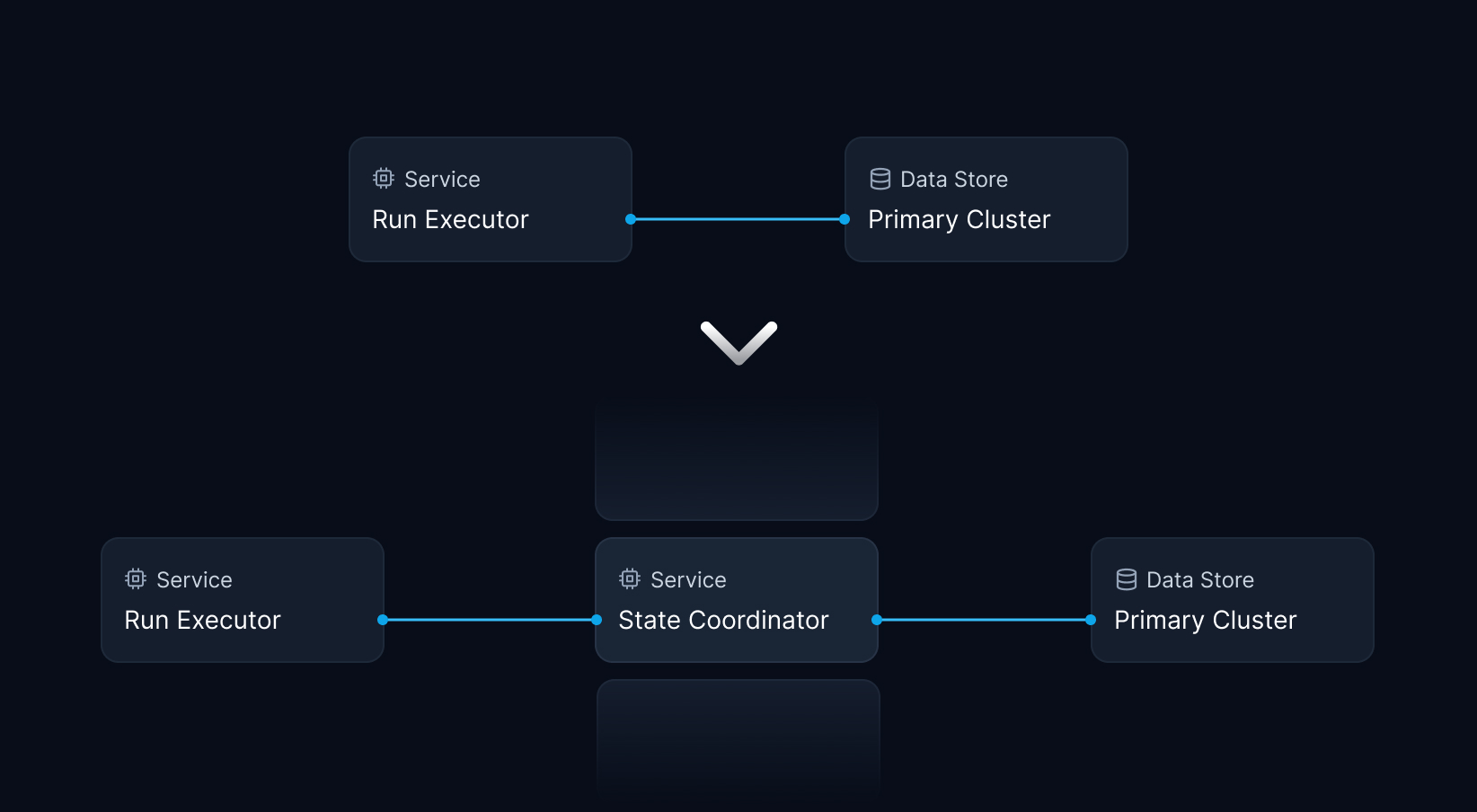

Our first phase was to create a new interface layer that would coordinate how our core system interacts with the function state database. This groundwork would enable our new system design and sharding rollout strategy.

Launching the State Coordinator

Two weeks after starting at Inngest, I joined forces with Jack Williams, our founding engineer, and kicked off work on a coordinator service mediating access to the state store. The state store persists events, step outputs, and other metadata on every function run. As users can return blobs and other data from their function run steps, we need to ensure incredibly fast reads and writes to the state store to keep latency as low as possible.

Adding this service boundary would enable connection pooling, centralized instrumentation for observability, and a single cut-over point to roll out changes across different user segments. Long-term, this also allows us to replace the Redis-based storage backend with a more scalable system tailored to our access patterns.

Sharding Redis

Having swiftly rolled out the state coordinator to production, Jack and I moved our attention onto addressing the two big limitations of our previous single-cluster architecture: running out of storage capacity and blocking Redis' processing loop by handling too many queries per second.

Our primary cluster contained state powering various features, including function scheduling, control flow logic, and function run state. To support future usage growth, we had to make room for new data, either by scaling the existing cluster or spinning up new instances and sharding. Scaling by adding more machines to the cluster (horizontal scaling) or resizing the existing cluster (vertical scaling) was our preferred option to reduce implementation complexity.

Unfortunately, scaling the existing cluster was impossible without downtime. Resizing the machine would have incurred at least 20 minutes of system-wide downtime while adding another node could have caused automatic key rebalancing of critical system state, blocking the entire system for an unknown duration. Accordingly, scaling the existing cluster was off the table.

Designing, implementing, rolling out, and operating a proper sharding infrastructure takes time, usually multiple months. While we could have built medium-term plans for sharding, we weren't excited about the added complexity. Following the idea of “The Best Code is No Code At All”, we strived to use the tools we already had at our disposal instead of introducing even more potential points of failure.

The broker architecture pattern

Reading the Redis Clustering docs gave us the inspiration for a solution that could combine the best of both worlds: What if we could keep using our existing cluster as is, while routing new data to a multi-shard Redis cluster, effectively applying the broker pattern? In this scenario, we could extend storage capacity to serve for the next months and beyond, while avoiding any downtime. The new cluster would run multiple nodes to distribute CPU load, and we could easily add or remove nodes over time with minimal impact.

From Redis Clustering best practices:

Redis supports multi-cluster operations by partitioning data across multiple Redis nodes, where each node holds a portion of the total data set. This allows the cluster to scale horizontally and handle increased load by adding additional nodes. In Redis, data resides in one place in a cluster, and each node or shard has a portion of the keyspace. A cluster is divided up among 16,384 slots — the maximum number of nodes or shards in a Redis cluster.

For this to work seamlessly, we had to get three things right.

- Start using sharded keys (including a shard key in the key's hash tag) on the new cluster for all related keys to be assigned to the same slot. This was required to equally distribute slots across the cluster nodes.

- Ensure our system is compatible with Redis clustering. This involved refactoring any multi-slot operations in commands or Lua scripts to connect to one, and only one, cluster node.

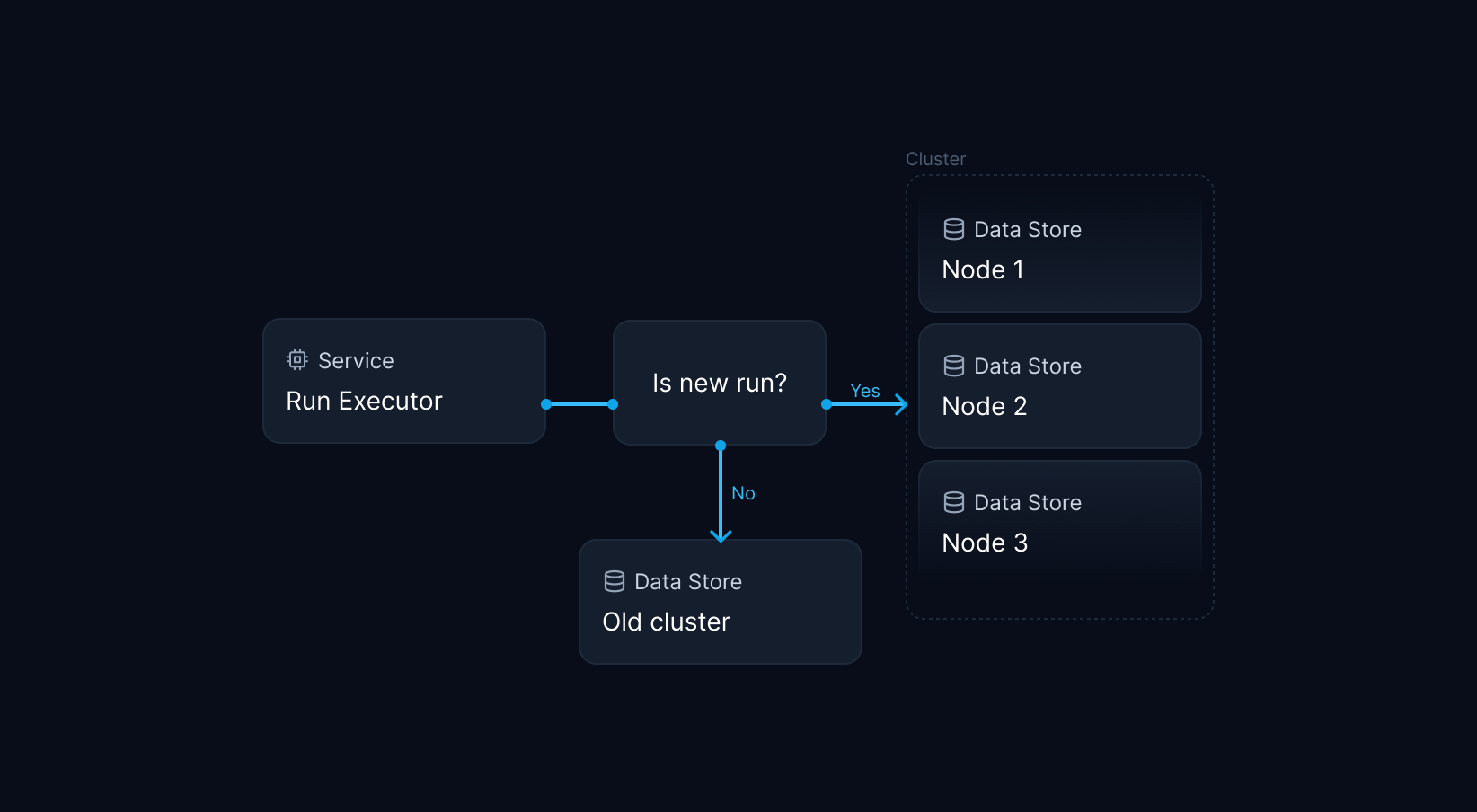

- Write rollout logic to start routing new data to the new cluster, while simultaneously enabling access to the old cluster for old data.

If we managed to solve these problems, we would get sharding out of the box. We could spin up a new cluster, roll out the sharding-enabled codebase, and immediately write new data to the new cluster while allowing old data to be consumed and deleted over time.

Running Experiments

To verify the feasibility of sharding our production data store, we conducted a number of in-depth tests. In particular, the system had to keep operating as expected while adding or removing compute and storage capacity in production.

Redis Clustering is interesting because data only ever resides on a single cluster node and its replica. This allows large Redis clusters to operate at incredibly high read and write volume with low latency and without giving up atomicity. Essentially, Redis clusters aren't much more complicated than running on a single machine. At the same time, adding or removing a shard requires rebalancing the cluster by migrating slots from one node to another. Redis does this using the MIGRATE command, which atomically transfers keys between machines, locking both instances for the time.

To prevent facing any locking delays, we decided against migrating any existing data or sharding the initial cluster in the first place. By running experiments against live clusters similar to our production instance, we verified that adding or removing nodes in the multi-node cluster did not have a significant impact on existing operations.

Implementing Sharding

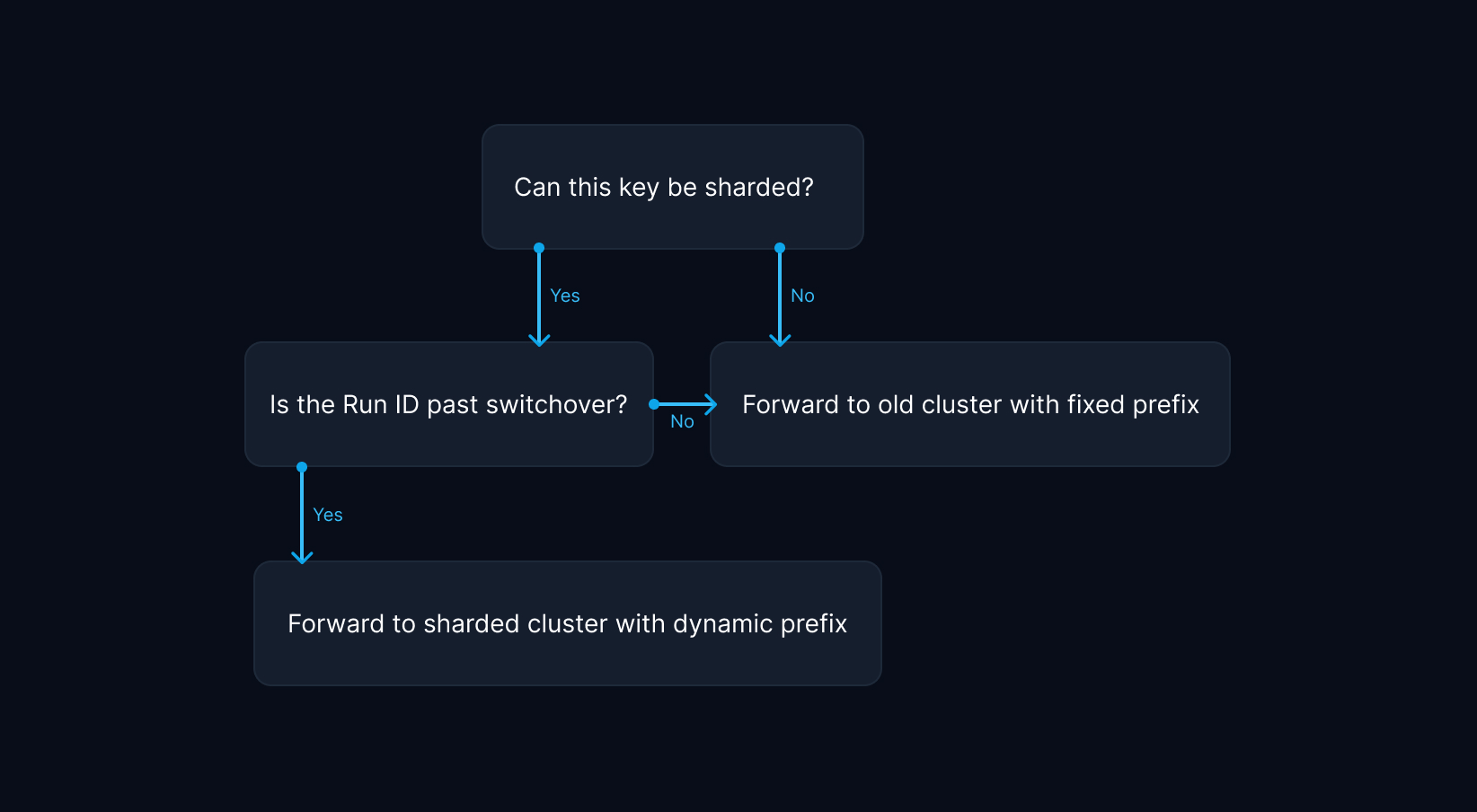

Once we were confident sharding would work, we started refactoring our production codebase to support sharding for function run state, the biggest contributor of large values in Redis. We updated our key generation logic to include a dynamic shard key for compatible keys as soon as the sharding condition was met. This was defined by passing a predefined switchover date, more on that later.

To ensure uniform data distribution across nodes in a cluster, sharding requires a suitable sharding key. The associated data should be as close to equal in size as possible to prevent hotspots, which lead to unbalanced utilization of available hardware. For instance, the Notion engineering team implemented sharding on workspace identifiers, while Figma uses multiple sharding keys for different product features. We decided to shard function run state by run identifier, which is available in all relevant access locations as part of the function run metadata. This is the most granular identifier we can use for sharding, which should yield the most uniform distribution of function run state.

To rule out any inconsistencies, we wrote tests to confirm key generation behavior would match the old codebase, when sharding was disabled.

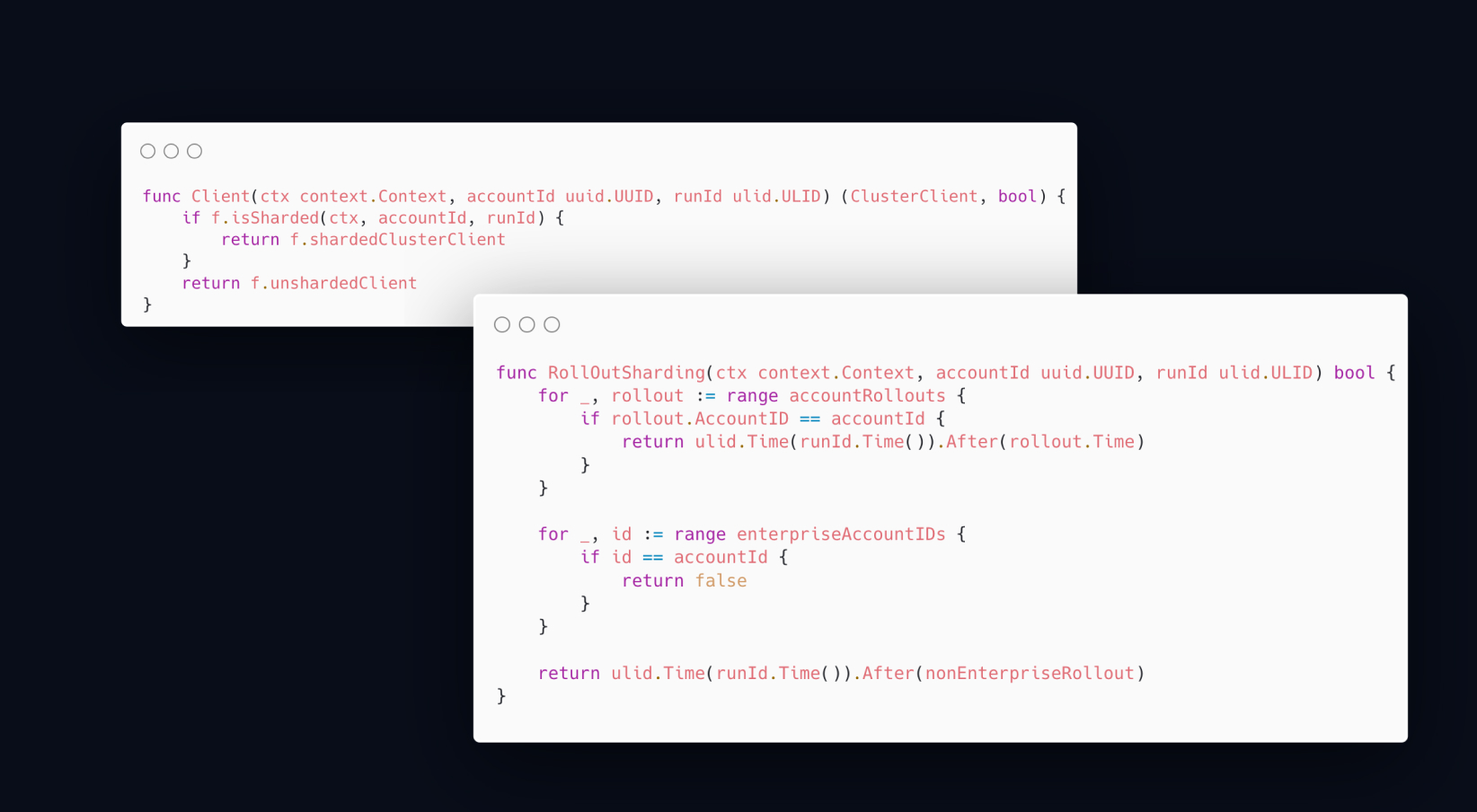

We also refactored our services to use multiple Redis clients where necessary and retrieve the correct client for a given entity based on the sharding policy. We associated Redis clients with product features to roll out sharding to other features in the near future. To prevent accidentally using invalid keys for a given client, we colocated key generation with client retrieval logic. This gives us compile-time guarantees about using the right keys with a client, while making it hard to use single-node keys on a multi-node cluster.

To avoid running into errors when using atomic Lua scripts with keys associated with different slots, we refactored existing scripts to operate on a single slot. For the majority of our operations, this was already the case. On a few occasions, we needed to introduce idempotency checks to prevent race conditions from performing the same instructions more than once.

Finally, we implemented special handling for transient errors encountered during scaling operations. This laid the groundwork to expanding compute and storage capacity whenever required.

Sharding Rollout

We provisioned a new multi-node cluster instance to serve as the data store for new function runs. The hard part wasn't making the old or new Redis code work; it was handling the state in between: We started by sharding function run state based on the run identifier. New runs should be created in the multi-node cluster, while old runs should be allowed to complete and get deleted from the old single-node cluster. All other data would remain on the old cluster.

Because deployments in a distributed system aren't predictable and old containers can run for several hours after rolling out a new release, we needed to ensure sharding would kick off as soon as every container was informed about the policy. Without perfect alignment, we could potentially flip the switch back for runs placed on the new instance, effectively breaking new runs.

We considered using a feature flag to provide the time at which runs should be written to and read from the new instance. Unfortunately, failing to connect to the feature flags backend would result in us using default values, drifting apart from previous state. This issue was inherent in loading any external data to determine the switchover date.

To solve the issue of aligning switchover times and reduce the risk of enabling sharding for everyone at the same time, we wrote a rollout policy as part of the codebase. Compiled into the same binary as the production services, the policy would be immediately available on rollout.

Similar to our state coordinator rollout, we designed the rollout to occur in multiple stages, affecting various customer segments, starting with free-tier users and ending with enterprise customers.

Once we successfully deployed the new code and monitored the system for potential issues, we felt confident to enroll Inngest's own production account for sharding on the same day. On the minute of hitting the switchover, new data appeared in the newly-created cluster. We were ecstatic.

Considering sharding efforts early and working on surrounding areas when the priorities shifted to delivering immediate improvements allowed us to kickstart efforts without a context switch.

Outcomes

We continued rolling out sharding for all non-enterprise users and decided to keep monitoring the system for any unforeseen issues before completing the rollout. A day later, we enrolled all enterprise customers to use sharding. The rollout was complete.

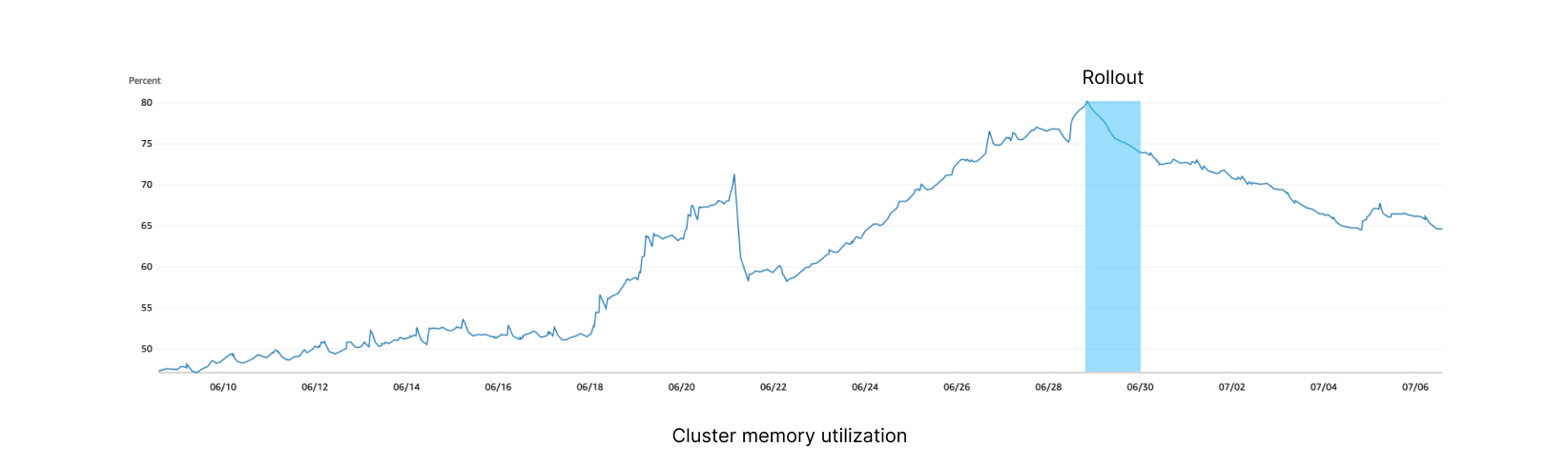

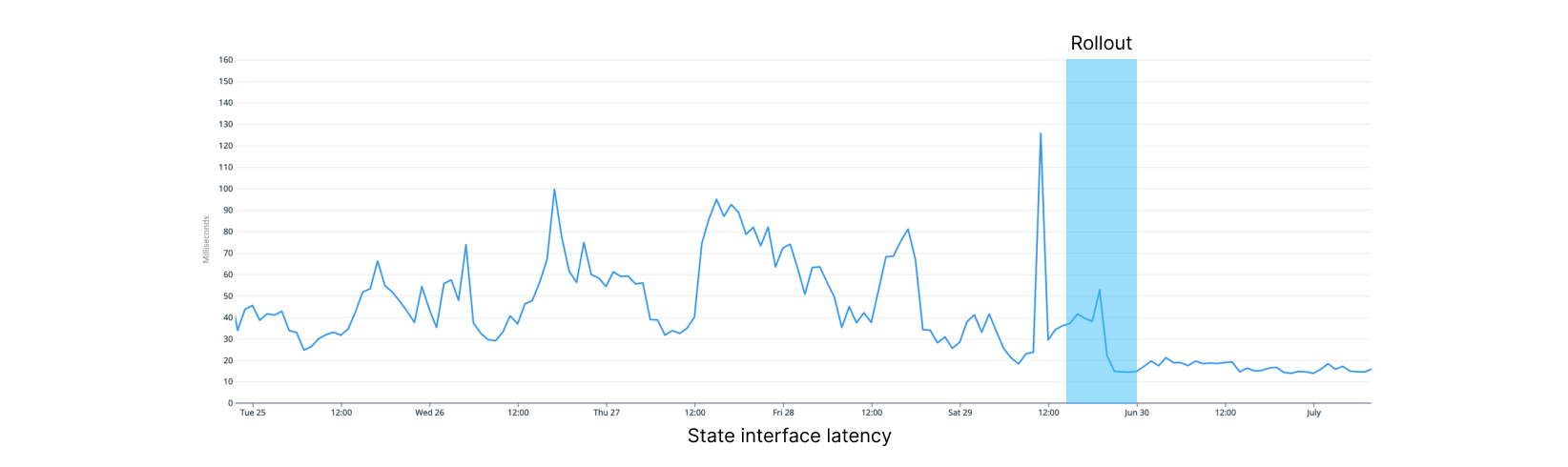

Within minutes of rolling out, our memory utilization stopped increasing. While CPU utilization stayed high during rollout, it decreased over the week, likely due to old function runs completing.

We are seeing 80% fewer timeouts during traffic peaks, and latency has progressively dropped from a volatile 35-50ms down to 7ms without any spike, presumably due to lower CPU utilization. As we continue to offload the previous instance and utilize the new cluster instead, we see higher performance and stability across the board.

These improvements extend to the entire system, so end-to-end operations will be consistently faster for all customers. And we didn't have to deliver a custom sharding implementation which had a higher probability for error-prone logic. All things considered, this effort was a massive success, preparing the grounds for more extensive infrastructure upgrades in the weeks to come.

Credits

Getting to this place was truly a team effort, in particular I want to thank Jack for teaming up with me. We implemented sharding in a week and rolled it out to production without a millisecond of downtime. This wouldn't have been possible without all the previous work by Tony, Darwin, and the team.